A young woman has become a symbol of the country’s silent mental health crisis. A survivor of sexual violence, she spoke publicly about her experience, hoping to find strength and perhaps understanding. Instead, she met a wave of hostility.

Since giving birth to a child, she has faced relentless online abuse. Every detail of her private life has been debated and mocked. Few stopped to consider her pain, or how public shaming might reignite trauma or trigger postpartum depression. Her story exposes a wider truth. Our culture of judgment and neglect leaves many people suffering in silence.

Today, as the world marks World Mental Health Day under the theme “Mental Health at Work,” Sierra Leone stands out for how little attention mental health receives. Despite years of recovery from war and disease, psychological well-being remains at the margins of public policy and social concern.

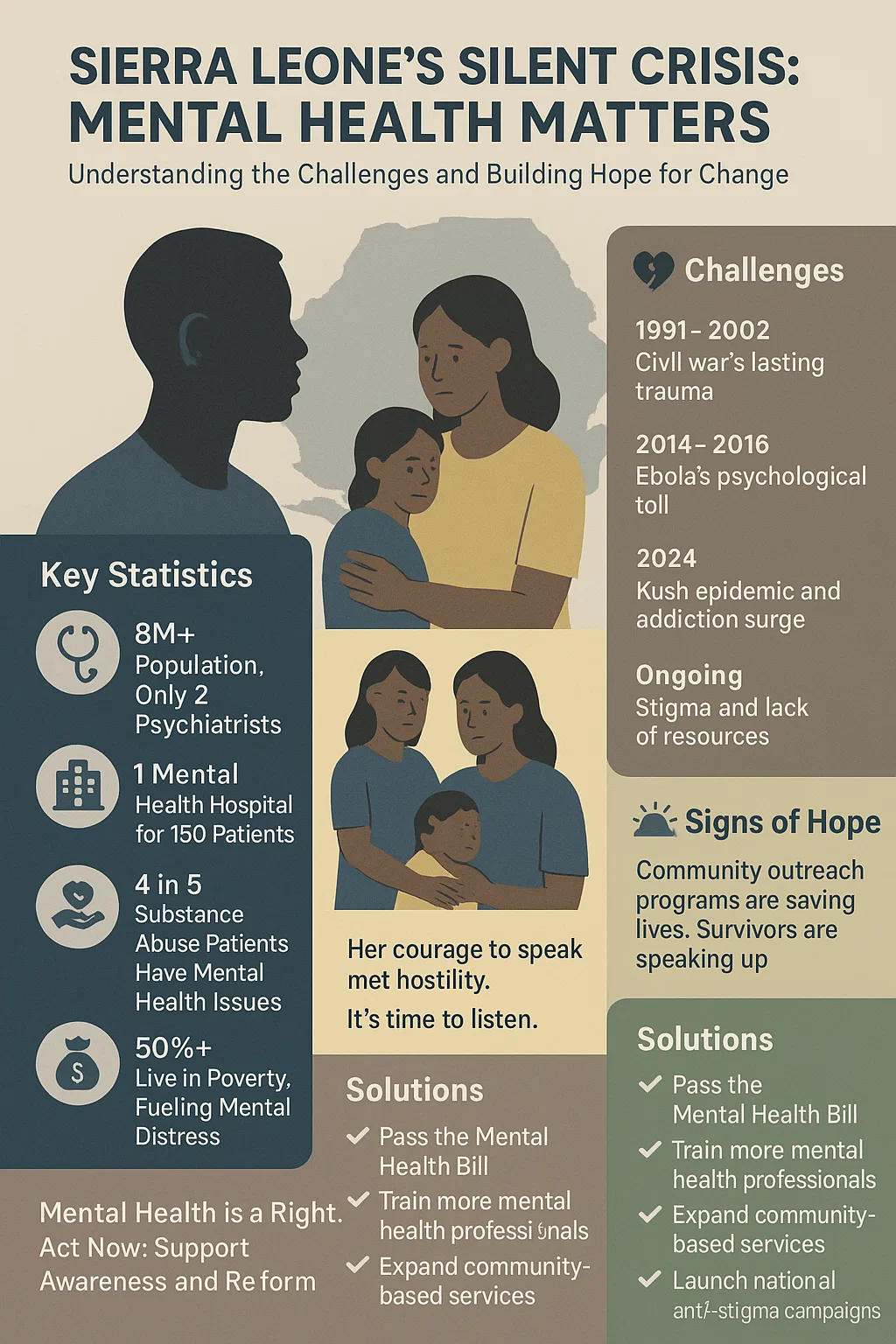

The numbers tell a grim story. For a population of more than eight million, there are only two psychiatrists, two clinical psychologists, and 19 mental health nurses. That means most people with mental health conditions go untreated. Many rely on traditional healers or are left to cope alone.

The situation reflects a deeper failure to see mental health as part of national wellbeing. Stigma, poverty, and neglect have combined to create a crisis that grows more serious each year.

The scars of civil war still run deep. Between 1991 and 2002, the conflict displaced millions and exposed communities to violence, loss, and fear. Research shows high rates of post-traumatic stress disorder and depression among survivors. Children of those affected often inherit that trauma, suffering anxiety and behavioural problems.

Economic hardship adds another layer. More than half the population lives in poverty. Youth unemployment is widespread. The daily struggle for food, housing, and work wears people down. Mental distress is treated as weakness rather than illness.

The Ebola outbreak between 2014 and 2016, followed by COVID-19, left more people isolated and grieving. Health workers who cared for patients also faced psychological strain, with little access to counselling or rest.

Now the rise of “Kush” has worsened the country’s mental health burden. Declared a national emergency in 2024, the Kush epidemic has fuelled addiction, psychosis, and suicides, especially among young men.

At Koidu Government Hospital, four in five substance abuse patients also have a diagnosed mental health condition. Doctors report overcrowded wards and families unable to afford treatment. Many patients relapse soon after discharge because community support is almost non-existent.

Without intervention, this crisis risks collapsing the fragile healthcare system.

We have only one mental health hospital. It holds about 150 patients at a time. Conditions remain poor, and staff shortages are severe. Many patients are restrained during episodes of distress because safer alternatives do not exist.

The government has launched small awareness projects. Africa CDC has urged lawmakers to pass a long-delayed Mental Health Bill. Many other are trying. Yet these efforts are far from enough.

Most mental health workers operate with minimal resources, often unpaid for months. Community clinics rarely include mental health services. Families bear the burden, caring for relatives without guidance or support.

The story of the young woman shows how stigma deepens pain. Many Sierra Leoneans still view mental illness as weakness, sin, or a curse. This stops people from seeking help. Victims of violence or trauma, especially women, are often blamed rather than believed.

Public discussions about mental health are rare. When they happen, they can turn cruel. On social media, cases like this young woman’s become entertainment. Few think about the emotional damage such attacks cause.

This pattern extends beyond individuals. In workplaces, sexual harassment and exploitation often go unchecked. Women suffer anxiety and depression in silence, fearing shame or dismissal.

Until the country confronts these attitudes, recovery will remain out of reach.

Sierra Leone has the chance to turn this crisis around. Change will require leadership, funding, and compassion.

Sierra Leone needs bold and immediate action to confront its growing mental health crisis. The government should pass a new Mental Health Bill to replace the outdated Lunacy Act of 1902. More doctors, nurses, and counsellors must be trained to provide psychological care across all districts. Community-based services should be expanded so support reaches people outside Freetown.

Drug treatment and rehabilitation programmes must be strengthened to respond to the Kush epidemic. National awareness campaigns are needed to challenge stigma and promote understanding. Media, schools, and faith groups should work together to build empathy and encourage open discussion about mental health.

There are small signs of hope. Programmes that combine psychosocial support with community outreach show that progress is possible. Survivors who speak up, like the young woman at the heart of this story, remind the nation what courage looks like.

Mental health is not a privilege. It is a right and a public necessity. We cannot build a stable and fair society while its people suffer unseen.

Every person deserves care, respect, and dignity. The young woman’s experience should not end in silence or shame. Her story should move us to act, listen, support, and reform a system that has looked away for too long.

Only through compassion and commitment will the country begin to heal the wounds that war, poverty, and prejudice have left behind.